A carriage once drawn by four horses now stands in the carriage shed at the New Haven Museum’s Pardee-Morris House, a symbol of New Haven’s industrial past nestled within a symbol of its colonial history. The carriage, which is not on public display, had spent its active life in the possession of a wealthy planter in Louisville, Kentucky, but it had first rolled out of the Lawrence, Bradley & Pardee company’s factory on Chapel Street before the Civil War. In LB&P’s 1862 catalog, the model is described as a Scroll Back Quarter Caleche Coach, in part for the luxurious length of its chassis, with a starting price of $800 (almost $24,000 in today’s money). A sugar bowl-shaped cabin is fitted like a jewel into a deceptively elaborate setting of spokes and springs.

At the time of the catalog’s publication, New Haven had 50 carriage manufacturers employing 10% of its working population, rendering it the nation’s leading carriage builder. New Haven concurrently led the nation in multiple industries, in part because it was both a harbor and a railroad hub. Raw materials steadily flowed and rolled in, and finished products likewise left in all four directions. Carriages could be shipped on the day of their completion, particularly to cities along the coast but also to customers as far away as the West Indies and South America. Railway stations and ports also fueled the carriage industry by creating a mandate for good, wheel-friendly roads to take people to and from them.

sponsored by

It was improvements in roads—or more accurately the emergence of country roads from wilderness paths—that prompted the emergence of the first carriage manufacturers after the Revolutionary War. According to Richard Hegel’s Carriages From New Haven (1974), the New Haven and Hartford Turnpike Company was incorporated in 1798 to connect the two co-capitals, another in 1802 to connect New Haven and Milford. Seven years later, James Brewster, a carriage-building apprentice en route from Boston to New York, strolled into the Orange Street carriage shop of John Cook—ironically, after his own coach had broken down—and saw New Haven’s potential as a carriage industry powerhouse. In the process of starting his own carriage shop, first on Elm Street, eventually on 23 acres at the east end of Wooster Street, Brewster established what was essentially a carriage-making district. He became what might now be called a developer with an interest in carriage-making, making it easy for other carriage makers to build factories on his real estate. That district—factories interspersed with workers’ houses, new and improved roads, saloons and boarding houses—became known as Brewsterville.

But the thing that made New Haven a kind of Detroit of carriage-making was its innovation in quality control and productivity. Whereas John Cook and his contemporaries oversaw the work of a single team of interdisciplinary carriage builders, the Brewsterville factories typically divided the labor into departments. Carriages in construction were moved by stack elevator to floors separately occupied by wood benders and carpenters, painters and varnishers, blacksmiths, finishers and inspectors. (Published in an 1879 issue of Scientific American, an illustration of the last of these shows four men severely poised on the carriage seats while a fifth jumps up and down on the carriage floor.) G. & D. Cook & Company—apparently unrelated to John Cook—explained this division of labor in boosterish terms, their “work being so arranged… that each workman devotes his whole time and capacity to doing a single thing, and… devising new ways of doing that thing simpler, better and cheaper.” With its army of specialists, G. & D. Cook & Company was said to produce a new carriage every hour.

In the same period, whole companies had emerged to compete with others’ individual departments. Alongside the 50 carriage manufacturers in 1860 were 38 more manufacturers of carriage parts. Dann Bros. & Co. began as a specialist in using steam to bend wood and expanded from there. Their 1881 catalog likewise touts their business model: “the manufacture of different parts—bolts, springs, axles, wheels, carriage parts and bodies… suppl

Like an automobile, a carriage was valued insofar as it offered a stable ride, so many of the local patents pertaining to carriages concerned their undercarriage. A German-born New Havener named Gustavus Haussknecht invented a mechanism that steered the front axle from behind so the carriage could turn corners with less chance of capsizing. And a former Revolutionary War captain, Jonathan Mix, invented the steel axle-tree spring, an upturned bow of iron connecting the ends of the carriage body to the middle of the axle, which redistributed the bounce from each wheel. He is said to have taken his family for a ride around the New Haven Green to reassure them by dint of its smoothness that their fortune was secured.

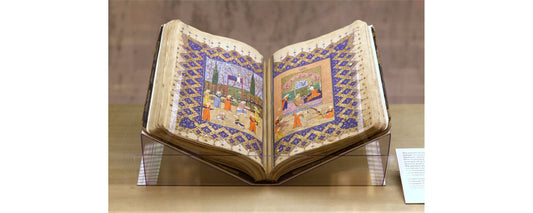

New Haven carriage makers also vouchsafed a comfortable ride with appointments to the interior. The carriage at the Pardee-Morris House is nothing less than a tiny carpeted drawing room entered through curved wooden doors. Decorously framed windows boast curtains to be raised or lowered for the haughty inspection or shutting out of city riffraff. Brass slots are, presumably, for the exchange of perfumed letters and invitations. Embroidered sashes for steadying oneself on hairpin turns hang from the walls beside cushioned couches with embroidered upholstery. The bowl of the carriage is rendered in wood planks steam-bent into elegant curves, painted and varnished to a rich dark brown, and trimmed with hand-carved vines and florets.

New Haven carriages were no ox-carts. It was in part the emerging competition from midwestern cities that drove New Haven manufacturers more decisively into the luxury market. The Civil War had struck a hard blow by taking away the brisk business New Haven was doing in the south. But carriages were also being made more cheaply and with greater access to lumber in Indiana and Ohio to both fuel and enact the country’s westward expansion. According to Hegel, the American Carriage Directory of 1886 credits the Cincinnati factory of one Mr. Lowe Emerson with being the first to use interchangeable parts—as if the city of Eli Whitney and James Brewster had only ever been good for planting its notable Elms. The final blow was, of course, the emergence of the horseless carriage.

By the time William S. Pardee had acquired his Scroll Back Quarter Caleche Coach in 1916, it was already a quaint curiosity from another era. His grandfather had been a partner in the firm that made it, and the New Haven Register’s contemporaneous account of the purchase suggests it had been drawn in its day between homes in Louisiana and Kentucky. The seller had first hoped it might be sold to a movie house for use as a prop in “ante-bellum productions.” Pardee thought he might fix it up and use it for “fun on the streets” (call it a Pardee wagon) with fellow New Haveners watching in nostalgic amazement.

“Old residents… recall the days before the war,” noted the Register, “when four horses pranced in front of it as the ladies went out for their drives.” Unsaid is that some of those residents may have had a hand in making it.

Written by David Zukowski. Image 1, showing the Pardee carriage circa 1921, provided courtesy of the New Haven Museum. Image 2 features the 1862 catalog version of the Scroll-Back Quarter Caleche Coach. Images 3 and 4, featuring the carriage today, photographed by Dan Mims.