The floorboards squeak, and the windows can be drafty. This 1827 boarding house wouldn’t be most people’s idea of a dream office. But Chris Wigren, Jane Montanaro and the small staff of the Connecticut Trust for Historic Preservation, a private nonprofit with ties to the State Historic Preservation Office, feel quite at home in the white clapboard house at the corner of Whitney Avenue and Armory Street, just over the Hamden line.

Rain is spattering against the 12-over-12 paned windows when we sit down in the front conference room—once a dining room, most likely—to talk about the work of the trust. Retaining historic spaces like this one is what the organization is all about. Its own history dates to the 1970s, when it was founded by three concerned preservationists from different parts of the state—Harlan Griswold of Woodbury, Barbara Delaney of Chester and John Reynolds of Middletown—who “realized that sometimes government agencies can’t be as flexible” as a private organization in responding to preservation needs, Wigren explains. Originally located in New Haven as a geographical balance to the state’s Hartford office, the Connecticut Trust moved to its current location in 1989.

sponsored by

Historic preservation is important to different people for different reasons, Wigren says. People may be looking for a “sense of connection with the past, … a feeling of connection, of continuity.” For others, the appeal is aesthetic or economic, perhaps earning tax incentives that have been built into the system or securing steadier property values. Still others appreciate what Wigren calls “the green aspect. It’s recycling through using things that are already in existence.”

What counts as historic is a moving target. The National Register of Historic Places says a building must be 50 years old before it can be considered. That puts Mid-Century Modern buildings in the category of “historic” today, a far cry from its past definition of Colonial homesteads and Victorian mansions. “In the beginning, preservation was a reaction against Modernism,” Wigren says. “I can remember some of the first times we started talking about Modernist buildings and getting pushback from people who were saying, ‘Wait a minute. That’s what we were fighting against.’”

Times and tastes are constantly changing, and the Connecticut Trust seems to be keeping up. Hardly purist, the organization has discreetly installed solar panels on the roof of their office. “We were trying to show that historic buildings can adapt

Minimizing potential damage is an important piece of the trust’s ongoing work. Sometimes it’s successful, as when it helped to save a Modernist library in Suffield, Connecticut, from demolition, or when it worked with SNET to place a preservation easement on its Art Deco Church Street building before it was converted into The Eli apartments. The easement ensures the building won’t be altered without the advice and supervision of the trust. Also under a preservation easement with the Connecticut Trust is a group of three 19th-century buildings on the corner of Chapel and State Streets.

Not every battle is won. Last year, despite the efforts of the trust and other local historic preservation groups, Quinnipiac University demolished four historic homes on Whitney Avenue, though two others were spared. The trust also recently lost its fight to protect a Westport home designed by famed midcentury architect Paul Rudolph. Its website lists other historic buildings slated for future demolition, saved for the moment by a state law that allows towns to impose a delay in order to buy time for negotiation of other solutions, Wigren says. Currently on the list in New Haven is the Yale Armory at 40 Central Avenue, built around 1940. The independent New Haven Preservation Trust is leading that conversation, Wigren says.

Occasionally, the fight to save a building goes all the way to court, as happened recently in New London, where the community wanted to stop a property owner from tearing down a building in the middle of its downtown historic district. The suit, brought by the state attorney general, favored the city’s wishes, but future use of the building is still a contentious issue, Montanaro says.

One way the trust keeps its finger on the pulse of history is through its archaically named “circuit rider” program, run in partnership with the State Historic Preservation Office. Two employees travel the state not by horse but by car, to meet with “property owners, municipalities

Other common questions relate to legal restrictions on building alterations, which are often misunderstood, Wigren says, partly because there are four different designations for historic structures, each with their own regulations. National Historic Landmarks and buildings on the National Register of Historic Places have no restrictions except against demolition, he explains.

There are no restrictions at all on buildings listed on the State Register of Historic Places. Only Local Historic Districts carry requirements for design approval of exteriors. New Haven currently has three of these districts, in Wooster Square, City Point and along the Quinnipiac River.

With so many issues to balance and so many projects statewide, there are always new challenges, Wigren says, and “always new things to discover” as history marches on. “…

CT Trust for Historic Preservation

940 Whitney Ave, Hamden (map)

(203) 562-6312 | web@cttrust.org

www.cttrust.org

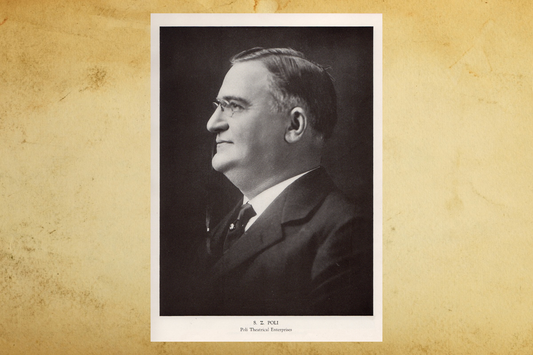

Written and photographed by Kathy Leonard Czepiel. Image #1 depicts Chris Wigren and Jane Montanaro.