Time is always on Carlos Eire’s mind, but not necessarily his side. The former is clearest in his academic work as a Yale historian, the latter in his popular memoirs about growing up in Cuba during the waning days of Fulgencio Batista’s regime and later in the US as a refugee.

Eire was one of 14,000 Cuban children airlifted to the US without their parents following the revolution that brought Fidel Castro to power. It’s no wonder that a man whose own history was torn in half—the life in Cuba and the life in America, with no possibility of return because he is now “an enemy of the state”—would be obsessed with time. The words “immortal” and “eternity” show up again and again in Eire’s writing, most prominently in A Very Brief History of Eternity (2010), a historical survey of humanity’s conception of eternity and how it’s influenced our behavior.

sponsored by

In that book’s Acknowledgments section, Eire makes the connection between his subject and his lived experience: “All of my life, for as long as I can remember, I have puzzled over death, which has always struck me as the greatest injustice of all, and so senseless,” he writes. “Maybe it has something to do with all those executions I saw broadcast on live television when I was a small boy in Havana, courtesy of Fidel Castro’s revolutionary ‘justice.’ Maybe not…”

Eire was 11 years old when he and his brother, Tony, said goodbye to their parents and boarded a flight for Miami. Though their mother intended to follow them, her visa was cancelled following the Cuban missile crisis, and it was three years before they were reunited. Eire never saw his father again.

Until the revolution, Eire had lived a comfortable middle-class boyhood in some ways familiar to many: watching TV, building model airplanes, trying to avoid schoolyard fights. His memoir Waiting for Snow in Havana (2003) tells the story of that boyhood in vivid, often funny detail. But Carlos the boy is also dogged by frightening dreams, and early in the book the family is caught in a New Year’s morning gunfight. He says it’s clear, in hindsight, that “something was about to snap.”

Writing a memoir was not on the academic Carlos Eire’s to do list. But he grew “increasingly disturbed” in 2000 by the story of Elián González, a Cuban boy whose mother had drowned trying to bring him to the United States. News reports, Eire says, missed “the elephant in the room, which was that this was not really a family dispute” over whether the boy’s relatives in Miami or his father back in Cuba should retain custody of Elián. Instead, it was a political dispute. “The Cuban government was claiming that every boy deserves to be with his father. That’s what drove me over the edge,” Eire says, “because the Cuban government prevented my father from leaving, and I never saw him again.”

Waiting for Snow in Havana won the National Book Award for nonfiction in 2003, a gem that’s buried in Eire’s Yale biography and that he says goes mostly unrecognized by his colleagues. He seems more amused by this than bothered. Seven years passed between that first memoir and his second, Learning to Die in Miami (2010), which picks up where Waiting for Snow leaves off: Young Carlos and Tony land in America and are separated. Before their uncle in Chicago is able to take them in, the brothers will experience the gamut of American foster homes, from kind and comfortable to violent and infested. The death to which the title refers is Carlos’s own, as he struggles to give up his Cuban self and become the American “Charles.”

As he watches the surge of news about refugees today, Eire notes, there’s a “sameness” to their experience. “Refugees leave everything behind and risk their lives, often. It’s a terrible turn in anybody’s life,” he says. “I know what these people are going through.” However, he adds, the situations that create refugees are unique.

Eire’s memoirs provide a vivid, particular and often entertaining as well as horrifying peek into an important event in recent history that is resonating again today. But his academic interests reach back much farther, to the late Medieval and early Modern periods. His most recent book, Reformations (2016), examines “Western civilization’s transition from the Middle Ages to modernity,” as the publisher, Yale University Press, puts it.

Eire recalls the moment he “became” a historian in Learning to Die in Miami, when he and Tony, who wander Miami’s streets in order to avoid their foster home, stumble across a “tiny branch” of the public library. His library card becomes like a “passport to the past and the future” to “replace

There are many passages like this one, especially in Learning to Die, in which young Carlos puzzles over his place in the cosmos and the strange movement of time: “As I scheme ever more intensely to kill Carlos, time acquires a whole new feel for me. I have no past, and no future. All I have is the present, which is eternal,” Eire writes. “The world has a past, which I’m beginning to discover as I grow ever fonder of history. But I have no past at all…

Eire attributes his fascination with death and eternity, in part, to a pre-Vatican II Catholic upbringing. “This life is just like a blink of an eye,” he says, “but what you do in this little blink of an eye determines how you spend forever,” he says, drawing out the word dramatically. “So you have to be very careful during that blink of an eye.” To complicate matters, his father was both Catholic and a theosophist who believed in reincarnation. In his memoirs, Eire often refers to his father as “Louis XVI”—one of the past lives he claimed.

Eire’s academic career—he earned his doctorate in history at Yale in 1979, taught at St. John’s University and the University of Virginia, then returned to Yale to teach in 1996—seems to have given him the greatest outlet for exploring these questions of life and death. In A Very Brief History of Eternity, he traces human conceptions of eternity from early Christianity (and its roots in Platonic philosophy and Judaism) to the relative present, bringing into the conversation the likes of Vladimir Nabokov, Sigmund Freud and Kurt Vonnegut and, representing the voice of the ordinary American, the results of contemporary polls on beliefs about an afterlife.

We’re all affected by notions of eternity “whether

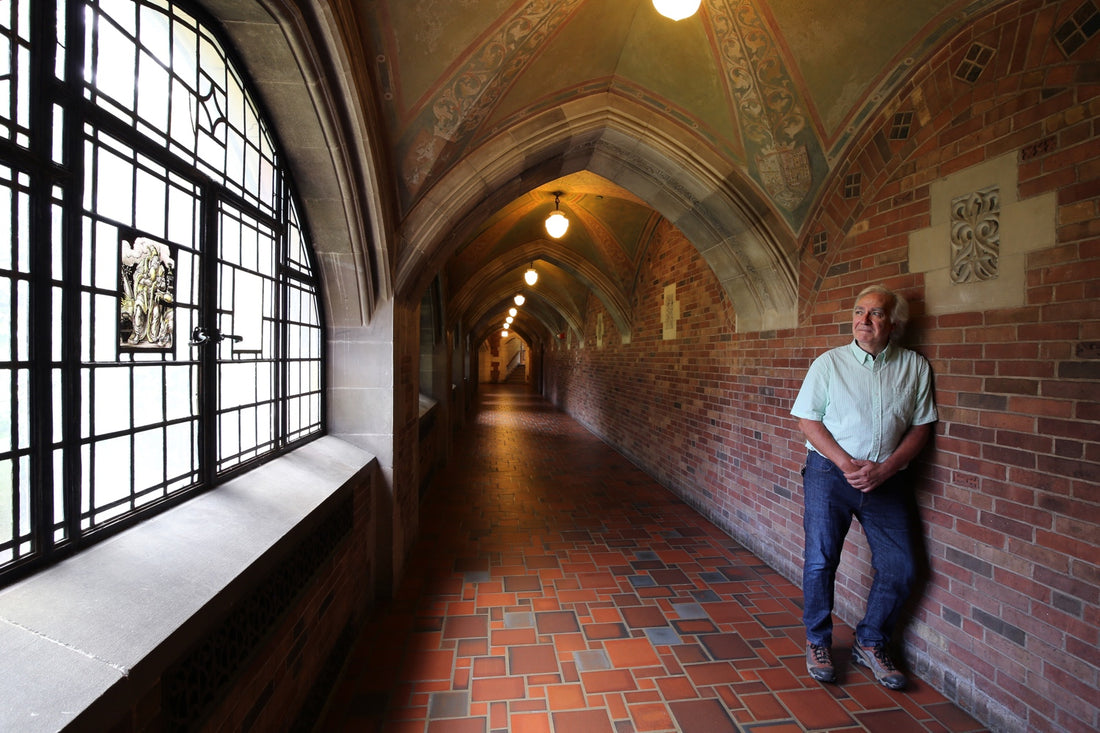

Carlos Eire

carlos.eire@yale.edu

www.history.yale.edu/people/carlos-eire

Where to Buy: Amazon | Barnes & Noble | IndieBound | RJ Julia

Written by Kathy Leonard Czepiel. Photographed by Dan Mims.